I’ve been visiting Kew Gardens – like many people I’m sure – since I was a little boy and have been at least once a year ever since. Increasing to multiple times now that I’m a professional horticulturist because it’s doubley useful for my work (I also really enjoy it). With each visit, a small part of me held a little regret that I hadn’t ever had a chance to work there. I imagined researching plants and going on jungle adventures around the world to examine plants and collect seed in their various habitats. I’d always wondered what the botanists were up to, in their secret areas away from the public – though of course the public areas do house plants used for research too.

So when my friend Laura arranged for me to have a sneaky peak behind the scenes in areas not open to the public, I obviously leapt at the chance. Back in January I was lucky enough to be shown around by Greg Redwood, the head of glasshouses. Greg has held a number of different roles at Kew over the years and is intimately familiar with the goings on. There are multiple private labs, buildings and glasshouses, on this visit we explored the tropicals, cacti and succulents.

On entering the large complex of glasshouses tucked away in one corner of the gardens, I noticed an immediate air of seriousness about the place. A tantalising glass room filled to the roof with lush green is on the left but then you turn into the main corridor, somewhat spaceshipesque. Greg pointed to the computer systems controlling the climates I can describe only as reminiscent of HAL from 2001 A Space Odyssey (looks wise, it didn’t try to kill us or anything).

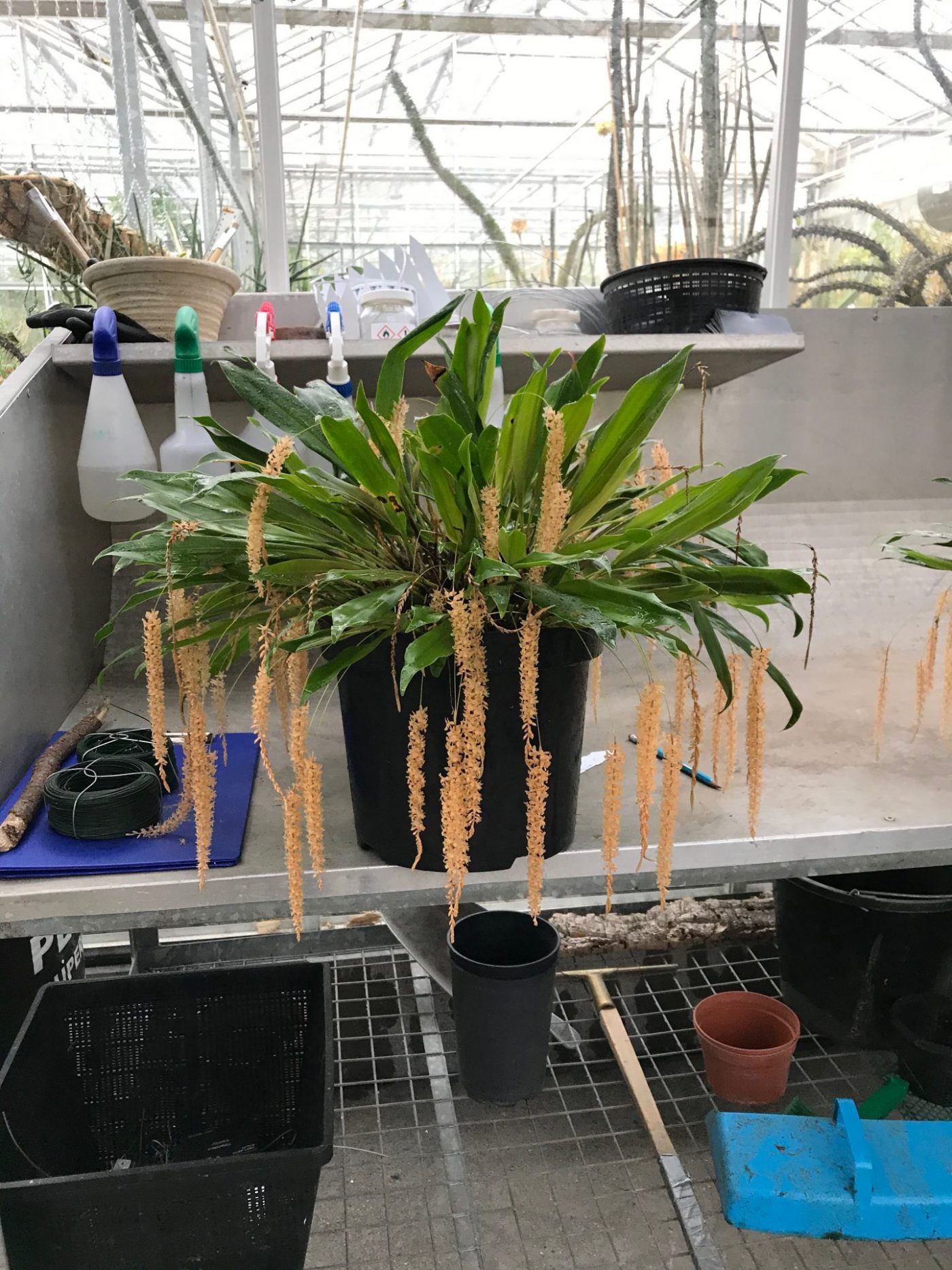

We started in the bromeliad zone before hitting on the orchid areas – as you can imagine, seeing the orchids was a giddying dream for me. Unlike the public glasshouses, these are arranged for growing rather than showing, so, many more plants are packed in and the variety is staggering. One orchid was meters in size, the largest I’ve seen, while others didn’t look like orchids at all. The very reason for Kew’s existence is for scientific purposes, on one hand, to study and understand all plant life on earth and on the other, to help safeguard that life for the future.

People at Kew aren’t growing these plants for fun or to sell in shops, they’re growing them to study, often for life saving reasons – many plants such as the aloes have beneficial properties for humans for food, medicines and more. A large number of medicines today are plant based or come from things we have learnt from plants. With so many diseases in existence still today, who knows what answers these plants will have for us as new medicines are discovered every day. The problem though, is that we’re wiping out most habitats around the world for these plants to survive.

The teams working in these glasshouses go to work everyday with the important job of keeping all of the species alive which often means propagating them to keep the generations of plants going. This is expert, precision work requiring huge amounts of knowledge about the hundreds of thousands of different growing combinations required. Each glass house managed by a dedicated team, logging every detail from watering, feeding, repotting, sowing and monitoring of pests and disease.

Really, I could have spent weeks in this place just examining each plant. The glasshouse network, is vast. With a footprint comparable to the Temperate House but with lots more species crammed in. Countless plants contained here are threatened in their natural habitats or already extinct in the wild.

I’m a sucker for carnivorous plants, always making a b-line for the little carnivorous plant room in the Princess of Wales Conservatory open to the public. Seeing the main propagation area for them was exciting and I was surprised to see species of drosera (sundews) as small as the tip of a pen. You can see them in the photos above alongside pitcher plants, including Nepenthes, with their flower heads covered to prevent cross pollination for later seed collection.

Adding to the space station vibes were the enormous blue water tanks under grow light. Kew Gardens grow the world’s smallest waterlily Nymphaea thermarum (as well as the largest) which is now extinct in the wild. Greg told me the story of the way their only habitat, a hot spring in Rwanda, was turned into a clothes washing business. Luckily, Carlos Magdalena who works here, figured out the plant’s complicated germination requirements and saved the entire species. The tanks also contained tiny new plants of Victoria amazonica and hybrids – the giant waterlily – ready to be moved into the public gardens in summer.

Every plant is carefully labelled and catalogued and it was exciting and sad to see so many with a red ‘critically endangered’ label. Exciting because here was something rare in front of me, saved by the many people caring for it but sad because so many species of plant and animal are in such a situation because of human activity erasing their homes.

We also popped into Kew Gardens’ famous herbarium with its 7 million plant samples, used by the world’s most famous botanists for nearly two centuries. It’s a beautiful structure filled with more information than one person could ever study in a lifetime. Right now the entire catalogue is in the process of being digitised to protect it for future generations – you can only imagine how big a job that is and one of the reasons Kew Gardens so badly needs increased funding.

As an interesting little factoid for you, it’s often in these herbariums that ‘new species’ are discovered or plant names change as the scientists find something Darwin and chums tucked away in a cabinet and forgot about. Retrospectively, the plant is then named or mistakes corrected. Of course, DNA analysis is, these days, making this process much more accurate and final.

All of this vital work, from glass house propagation to the herbarium cataloguing ties into Kew Garden’s most important mission, given life in the Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst Place, Kew’s second site. Here, in an underground bunker at low temperatures is a living archive of seeds from a majority of plants around the world. The mission being to include all of them for the future. This protects all plant life from whatever disaster may face it, human or naturally caused. It’s not a reason to think habitat eradication is OK because we can just grow a plant – habitat loss is a much bigger problem – but it is a safety net for a future that almost certainly will, at some point need it (those species extinct in the wild now rely on it to keep them going).

The seeds grown at Kew Gardens are used to keep species of plants going; plants don’t live forever so new generations are grown in organised tandem with the seed bank. Seed doesn’t store forever either, seeds are taken out to grow new plants at the right time, the plant then grown and pollinated to produce new seeds for the seed bank, and so on. Every plant is different the organisation needed incredible.

Food to support our near 8 billion population and growing, medicines to save us from the worst viruses and diseases, and plants that contribute to ecosystems all around the world with their intricacies we barely still understand. Kew’s work is more than the garden we see in West London and yet, in recent times Kew Gardens has lost almost 70% of its funding due to Government cuts, an action I can only look on as blindingly shortsighted.

You can help by, like me, becoming a member and visiting regularly – buying lots of their cake! Kew Gardens has a programme of events to attract more people to the garden which it needs to make up for the gargantuan shortfall in funding. Exhibitions such as the visually spectacular and popular 2019 display by artist Chihuly all help make a difference by drawing in the crowds.

For me, the trip behind the scenes was an exciting and fun one, thank you Greg and Laura for your time to make it happen. It also helped me to see how all of the different teams’ work is interlinked with one another. One team growing to keep plants alive and collect seeds to be stored to protect rare and endangered species, others cataloguing to share the information with other scientists around the world, while the Millennium Seed Bank team monitor and store the precious seeds.

Thanks for posting, teaching, and sharing with us. I went to Kew last summer, and will return again this summer. But I’ll not get to see the inside story as you have, so thanks mate for sharing.

Wow, that’s quite the place. Would love to see it in person. Thanks for sharing it!